Greenwich is located in the south east of London. Its name rings a bell for us because Greenwich is the name given to the Meridian of 0º longitude. Greenwich is also well known for its naval history.

A very good, comfortable and fast way to get there is by taking the MBNA Thames Clippers at the Tower Pier.

Greenwich National Maritime Museum

National Maritime Museum

This awesome Museum is set in Greenwich Park and it belongs to the Maritime Greenwich World Heritage Site.

There are many interesting things to see such as a flying boat called Miss Britain III designed in 1933 by Hubert Scott-Paine. It has a wooden and aluminium framed shell, coated in highly polished pure aluminium. This augmented her speed and withstood corrosion in salt water.

Miss Britain III raced against her American rival, Miss America X, in 1933 in the International Harmsworth Trophy in the USA. Miss Britain was narrowly defeated but her smart use of new materials in her design drove the paramount evolution of high-speed naval torpedo crafts and gunboats during World War II.

In the first floor we can admire the Figure Head collection with hundreds of figureheads and ships badges which show the ornamental carving of ships between the 17th century and the 20th century.

What is a figurehead?

Seafaring people throughout the world have always decorated the bows of their vessels. In ancient times, painted eyes, carved figures and animal heads were thought to enable ships to see their way. Vikings in northern Europe decorated their ships with dragon heads. The figurehead, as we know it, developed from this tradition. Sailors believed that they protected ships from the dangers of the sea.

During the 17th century, figureheads on naval warships depicted lions or sometimes warriors on horseback. In 18th century, Britain parliament restricted naval spending on ship carving but ornate figureheads continued and more closely represented the name of the vessel. During the 19th century figureheads also flourished on cargo ships but disappeared with the last wooden sailing vessels.

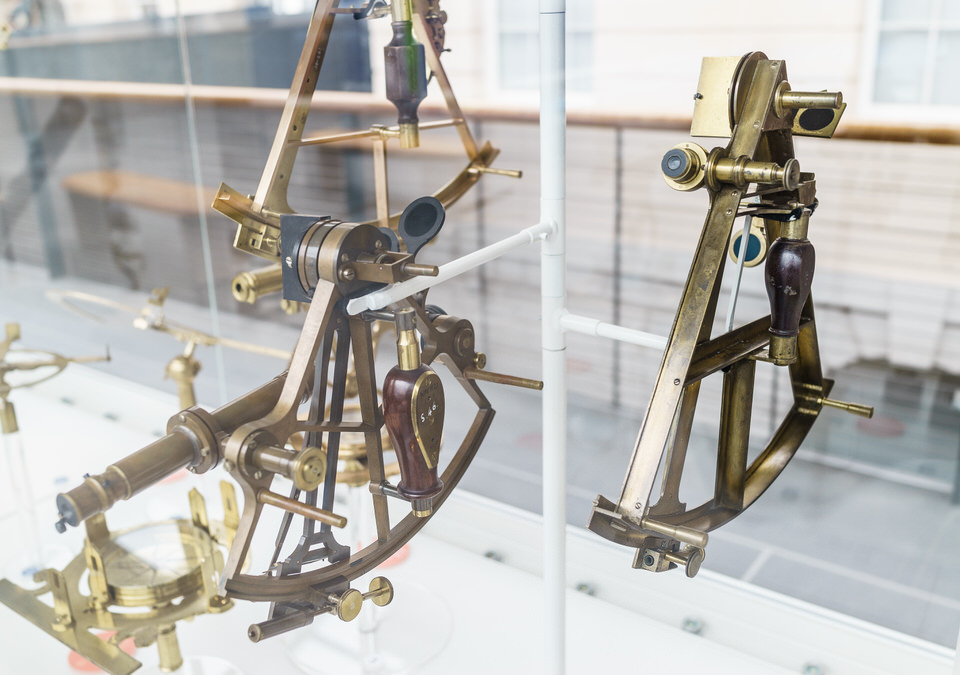

Navigation tools

Where am I going?

What should we do for remembering our position for the next time? We can record our position through instruments and charts but this is only one way of doing things. Other ways include remembering the stars on a globe or by heart. We can also jot down ‘sailing directions’ (notes of where to go and what to look for).

We all use landmarks -a bus stop or a building- to work out where we are going. How can you do that on the ocean with no landmarks in sight?

The Sun and stars are ’skymarks’. The Sun always rises in the east and sets in the west. At night, the Pole Star always mark north. Other stars move into view at different times of the year. We can track these stars to help us find where we are.

Using the Sun

Knowing which way the Sun rises and sets -which way is east and west- is the first step to finding your position. Sundials can help; for example, by showing the direction of Mecca, for Muslims to pray. The Sun is also a ‘skymark’ telling you the time. Most sundials have a gnomon (pointer) that casts the shadow. Gnomon is an ancient Greek word meaning ‘indicator’.

Using the stars

Stars are great ’skymarks’ -signposts in the sky that help you to find your way. A Greek astronomer named Ptolemy (AD 127-145) first named groups of stars as constellations, making them easier to find in the sky. Astrolabes (meaning ‘star catchers’) or simpler nocturnals (meaning ‘use-us-at-night) are like calculators. You can read the engravings on them to find Ptolemy’s constellations, latitudes, the date, the tie and stars at different times of the year.

Using depth to map where you are

If you have a chart with depths marked on it, and know the depth of water beneath your ship, you can tell where you are! Nowadays we mainly use sound waves to find out depth and map the sea floor, including to find wrecks.

How can I be sure where I am?

Before ‘satnavs’ (satellite navigation devices), people checked their location with protractors, compasses, depth measurements and clocks.

They could then be sure of how far they travelled east and west (longitude) or north and south (altitude). To see the stars more clearly and to help find their position they used telescopes and binoculars.

Seeing more clearly

It is easier to see the stars with a telescope or binoculars: but telescopes were not just for navigating. Some were used to help aim guns. Other were scientific accessories, bought by the wealthy to decorate their homes and show off their learning and good taste.

Measuring your position against known things

If you know the exact point where you started, you can measure how far you have gone. This helps you find your location. You can measure your position by calculating speed, distance travelled, time spent travelling, depth of water underneath your ship, or the angle of skymarks or landmarks that you can see around you.

Franklin’s lost crew #DeathInTheIce

In 1845, Captain Sir John Franklin, a veteran of the Battle of Trafalgar, sailed from England in search of the final stretch of the Nort-West Passage in the Canadian Arctic. Tragically, all 129 men on the expedition were to vanish without a trace.

Each flag represents one of Franklin’s lost men, many of them very young sailors. Their names, places of birth and ages are listed, as well as the positions they held in the crew. A memorial to the men who perished can also be found in the chapel of the Old Royal Naval College across the road.

The reasons for their deaths had remained a mystery for over 170 years, but after the recent discovery of the expedition’s ships, the National Maritime Museum is able to present Death in the ice: the shocking story of Franklin’s final expedition, 14 July 2017 to 7 January 2018.

Admiral Horatio Nelson

Whilst admiring the coat of Nelson, I was amazed by the story of one of the best known heroes of the UK. He was a great leader and strategist who harvested a great number of naval victories during the Napoleonic Wars. He was wounded many times in combat losing an eye and an arm and finally he was shot and killed during his final victory at the Battle of Trafalgar in the South of Spain.

Horatio Nelson became a midshipman in the Royal Navy at the age of 12. As with many young officers, he advanced through a combination of personal connections and skill.

However, it was Nelson’s talent for leadership that set him apart. In 1797 he showed great initiative during the Battle of Cape St Vincent.

The following year he defeated the French fleet at the Battle of the Nile. These famous victories established him as the outstanding naval officer of the time.

The death of Nelson

HMS Victory received heavy musket fire as it approached enemy ships at Trafalgar.

At 1.15 p.m., Nelson was hit in the shoulder by a musket ball fired from the mizzen top of the French ship Redoutable. It shattered his shoulder, punctured his lung and lodged in his spine.

The hole can be seen on the left shoulder of his uniform. Nelson knew immediately it was a fatal injury. Moments after he was hit he said to Captain Hardy, ‘They have done for me at last, my backbone is shot through.’

After Nelson was shot, he was carried down to the Victory’s dimly lit cockpit, on the orlop deck. There the sounds of battle and injured sailors were mixed with cheers from the crew each time an enemy ship surrendered.

Nelson lived for three more hours. Friends and close colleagues attended to him. Nelson’s chaplain, purser and steward never left his side. Captain Hardy visited twice, the second time to congratulate Nelson on a glorious victory. On hearing this news Nelson replied, ‘Now I am satisfied. Thank God I have done my duty.’

Private grief

Those close to Nelson were deeply affected by his death. Like most naval officers, Nelson spent much of his life at sea, far from loved ones at home.

He married Frances Nisbet early in his career but it was not destined to be a happy relationship.

In 1798 Nelson began a scandalous affair with Emma, Lady Hamilton. She was one of the most celebrated and glamorous women of the time, wife of the British ambassador to Naples. She was born into poverty. She rose to fame as a model, courtesan, dancer and fashion icon. Her relationship with Nelson helped to make them both the greatest celebrities of the day among the British public. Their affair lasted for the rest of Nelson’s life and they had a daughter called Horatia.

Causalties of war

Naval life was very dangerous. Disease caused most deaths at sea but, in battle, the crew faced death or injury in many ways. There were no safe places on board a warship.

When a cannonball hit a wooden ship’s hull, the timber could shatter into a storm of lethal, jagged splinters. Men could be crushed by gun carriages, hit by musket balls or wounded in hand-to-hand combat.

Casualties of all ranks were sent to the ship’s surgeon. He worked on the orlop deck, a space deep within the ship below the warterline. Conditions were often appalling and many patients did not survive.

Surgical set

Warships were well-equipped with surgical knives, catlins, forceps, bone saws, field tourniquets, to treat wounded sailors.

Men on the upper decks of a warship were particularly exposed to musket and pistol fire. Forceps were used to extract the lead balls these guns fired. Surgeons also removed tiny scraps of clothing carried into wounds along with the bullet, as they could cause life-threatening infections.

Amputation was the only treatment for severe injuries to seamen’s arms or legs. An amputation knife was used to cut swiftly through their skin and flesh down to the bone. These operations were performed without anaesthetics.

The catlin is a double-edged knife used to cut through tissue around bones or joints. Surgeons had to carry out these delicate operations in the noise and chaos of battle. They usually had an assistant. if women were on board ship they sometimes took on this job.

A bone saw was part of a naval surgeon’s standard amputation kit. After cutting through the patient’s flesh, the muscle of the injured limb was pulled back to expose the bone. This was then rapidly sawn through.

Trephination set with cranial elevator

Trepanning is a surgical technique used to cut a hole in a patient’s skull. The hole was made with a hand-operated drill to release pressure on the brain caused by severe head wounds. Once a section of skull had been drilled out it was lifted away with a cranial elevator.

Cutty Sark

It is a British clipper ship for tea and wool trade with China and Australia. It was one of the last and fastest tea clippers to be built.

It is listed by National Historic Ships as part of the National Historic Fleet.

She is located in Greenwich close aboard the National Maritime Museum. She was preserved as a museum ship.

Royal Observatory

Another interesting place to visit in Greenwich is the Royal Observatory that plays a paramount role in the history of astronomy and navigation.

It is located on a hill in Greenwich Park, looking over the River Thames. It gives its name to Greenwich Mean Time because it owns the location of the prime meridian.

I hope you have enjoyed this short summary about Greenwich.

No Comments